A bold and possibly heretical statement, but hear me out. In this age of photographers brought up with digital cameras that do auto everything, people expect their photos to be perfectly exposed and in focus, and it’s become even worse with the power of computational photography on the latest mobile phones. All these technological advances have made our tools incredibly powerful and capable of doing things we could previously only fantasise about. Digital sensors have not only become bigger but more pixels have been squeezed onto existing sizes, and are capable of recording in almost darkness. Lenses are faster and sharper than our eyes, and autofocus systems can not only recognise the eyes of humans but also different animals and birds, and continuously follow them, so that photographers can capture subjects in crisp focus that would have previously been near impossible. And different types of transportation were introduced on the Olympus OM-D E-M1X with a firmware upgrade. However, the result of all this technology is too many people are focussing on the technical “perfection” of the image and not on the actual content. If you’re pixel-peeping at the image’s sharpness, maybe it’s just not that good a photo in the first place. Folks are sacrificing the soul of the image for physical perfection, an affliction that seems to be permeating our culture and society in general.

All this fantastic new technology has led to many photographers who do not fully understand or know the fundamentals of the craft, or how to use a device in manual – much like American drivers with their cars. Some photographers will argue that there isn’t any need to know how to shoot in manual mode, whether it’s for exposure or focussing and, in many cases, some level of automation does speed up the process and guarantee usable (not necessarily good) images. Certainly sports and wildlife photography benefit from these advances, and the huge burst rates almost guarantee capturing the crucial moment, but is the final image really a testament to the photographer’s skills or that of the camera’s technology? It’s got to the stage where the photographer doesn’t even need to be anywhere near the camera, or the stadium for that matter.

Now, this is where I go into old man mode and rant about it not being like it was back in my day, which, as I’ve just pointed out, it certainly isn’t, but we still managed to get the shots back then. The bulk of the world’s most iconic and historical shots were made on fairly rudimentary equipment, compared to today’s technological wonders.

It was my love of surfing in the 1970s that got me truly hooked on photography, although I was already interested in it but not to any great extent. However, capturing the glorious waves along Australia’s coastline, with my mates and others riding them, meant not only having to up my equipment but also learning how to use it, spurred on by the dream of one day travelling the world working for a surfing mag. Shooting surfing from the land requires a telephoto lens. I started with a 300mm, moved up to a 500, before settling on a massive 800mm f/8 beast. These were all manual lenses, which meant learning how to follow focus while panning along the waves. At least I had an electric winder, so I didn’t need to move my hand to advance the film to the next frame. There were no high-speed sequential bursts (around 5fps was about the fastest with an expensive motor drive), it was always about waiting for the crucial moment before pressing the shutter, and hoping that focus was maintained. Even today, some 40 years later, I still occasionally dream about standing on the hill overlooking Kirra Point, but armed with an Olympus OM-D EM-1X and the stunning new Zuiko 150-400mm f/4.5 Pro lens.

Which brings me back to the point of this post. Back in those all-manual days we always aimed to get the shot in focus, especially if we wanted to see it published, but a great shot was a great shot. As I mentioned before, if you go and look at the iconic shots from photography’s history, especially in the fields of documentary and photojournalism – war, sports and live music in particular – many of them were “soft”. This could be either because critical focus was missed, there was blur from a slow shutter speed or the lens wasn’t as sharp as today’s glass. There was also film grain to consider. However, all these limitations were taken into consideration and accepted, especially if you nailed the shot. In fact, I would say it is the lack of those attributes in digital photography that is making the lack of pin-sharp focus and blur so unacceptable today. Those old limitations of film cameras gave the images their distinct character – the mathematical uniformity of digital noise is no match visually for film grain – but the story and composition were always far more important.

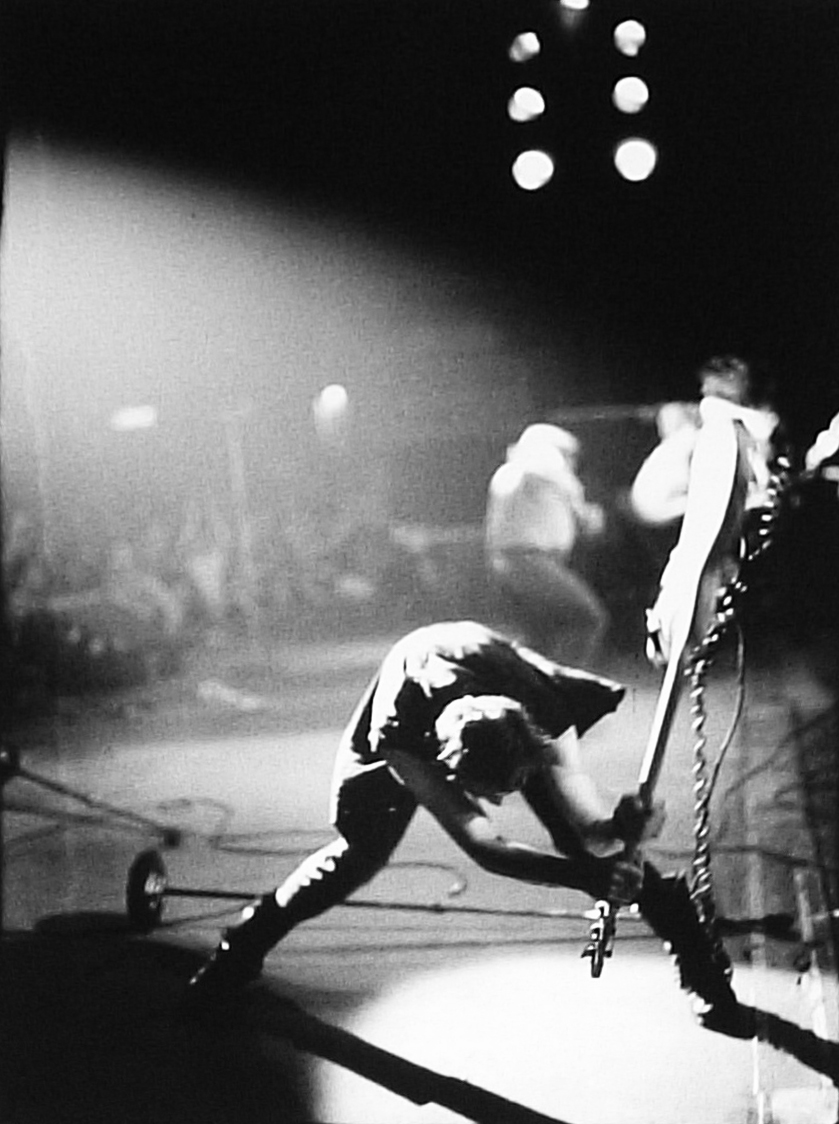

Look at what is considered the greatest rock photo of all time, Pennie Smith’s shot of The Clash that graces the cover of London Calling. It’s blurred and out of focus. The story goes that Smith was going to reject it because of that, but the band loved it and insisted on using it. The rest is history. You can buy an authorised archival print of it for £4000 from Snap Galleries.

© Pennie Smith

I have a decent library of photo books, especially from music/concert photographers and many of the live shots are slightly out of focus, and even some of the portraits. Looking at the Magnum Contact Sheets book, again there are many where the focus was missed slightly. Even greats such as Cartier-Bresson, Avedon, Klein and Peter Lindbergh would sometimes miss nailing the sharpest focus, but the images weren’t rejected out of hand for that, which seems to happen a lot more today. This is partly because of the exacting expectations from modern cameras to get it right every time, and increasingly so, without making allowances for human error, or intent.

Incomprehensibly, this obsession with sharp focus is coupled with the current ongoing fad for shooting wide open to get shallow depth of field and “bokeh” (the great HC-B said, “Blurred backgrounds in colour photographs are distinctly displeasing”), making getting “perfect” focus even harder. Micro Four Thirds cameras are often vilified for their lack of shallow depth of field, which is complete nonsense because the depth of field is the same for any lens of the same focal length and aperture. The main difference comes with the distance between the photographer and the subject, which, with M4/3, is extended due to the reduced angle of view because of the smaller sensor, meaning the photographer needs to stand further away to get the same framing as a full-frame sensor, or to use a shorter lens that will naturally have a greater depth of field. Personally, I actually welcome the extra depth of field that comes from using M4/3 when shooting live music. As the artists are always moving, having that extra bit of depth of focus comes in really handy, and concert photos aren’t supposed to be artsy studio portrait shots anyway, although they should be as well composed, lit and exposed as possible under the uncontrollable circumstances.

Of course, this leeway with focussing does refer to the more documentary styles and not to studio work, such as still life or portraiture, where there is plenty of time to set up the shot and get the focus correct. And, if you are using Olympus digital cameras, you have the options of focus bracketing and focus stacking built in, which not only means that you can get increased depth of focus but also keep those trendy “creamy bokeh” blurry backgrounds at the same time, if you want to. So, yes, if you are in one of those fast-moving situations where you might miss focus by a little bit, or get a bit of motion blur, don’t dismiss or cull the shot out of hand because of what the pixel peepers might say, but keep it in the knowledge that the greats didn’t always get it spot on either. As long as the intention is there, and it’s close enough, providing it’s a great image, you’re good to go. In the end, it’s your photo and your decision, and bowing down to the dictums of pursestring-holding gatekeepers is a good way to crush your creativity.

Pingback:Getting Out of Your Depth – Chris Patmore