Just like video killed the radio star, the web has pretty much killed the print industry. Or so we are led to believe. It’s true that huge circulations of the magazines that used to line newsagents walls have diminished, along with their advertising revenues, because people no longer rely on print media for their information. For music photographers this is extremely evident. Most of the glossy monthlies have now gone, even the grandfather of the rock press Rolling Stone is a shadow of its former self. There are (or were before the pandemic hit) a handful of free magazines, available from venues, that still catered for fans who are interested in alternative and underground music. These are, for the most part, run by volunteers and people that are happy not be paid, or to work for a fraction of what staff were paid in the print heydays. Blogs and online magazines are the main places people go to find out what is happening on the scene, and these too are primarily volunteer run. For photographers they are both a way of getting those elusive photo passes that allow pit entry, and (hopefully) a way of getting their work seen – the highly rated “exposure” that seems to hold more value than cash for those that offer it.

Apart from the lack of payment, there is another downside to shooting for the web only: the development of bad habits that don’t transfer well to the world of print, where a chance of being paid is still a possibility.

I started working in the creative industries before digital took over, and possibly before they were even called creative industries. As a graphic designer, everything was firstly visualised on paper. You had to calculate the type size needed to fit the words (supplied on paper) into the space on the page, or specify the exact word count to fit the space according to the type size. The article, with the type specifications marked up, would be sent to the typesetters, who would send back galleys of type to those specifications. These were then glued onto boards with the page template printed in on it. For photos or illustrations, a box would be drawn on the board and either a sketch of the required crop, or a photocopy of the image would be placed on an overlay so that the repro guy would know how big to scan the transparency or B/W print. Everything was designed to fit the page format, and we worked within those restrictions, even with the advent of DTP. Then the World Wide Web arrived. Most designers were still working with a page-format mentality, but we soon realised that those restrictions no longer applied. Journalists could write as much or as little as they felt like. There were no print costs to consider, which was the usual criterion for deciding the word and image count. As connection speeds improved, more pictures could be added to web pages without choking their loading times.

Nowadays, with WordPress and similar content management systems (CMS) becoming the default method of building web magazines and blogs, horizontal/landscape photos are the preferred format to fit in sliders and galleries. Because so many of the people working in the concert/gig photography world today have never had to shoot for print, there are lots of things they don’t take into consideration at the moment of pressing the shutter, which often makes their work unusable for print. OK, if it is a stunning, iconic shot then the designer will find a way to make it work within the layout, no matter what, but along with general “rules” such as avoiding mic face and not cutting off the neck of the guitar, here are some points to consider.

Don’t fill the frame or crop in camera. With all that is happening on stage, it is sometimes unavoidable if, say, the singer suddenly leans into the camera, or the guitarist does a spectacular jump in front of you. Ideally, you need to leave space around the action because:

- Not all magazine pages are the same ratio format as the camera’s sensor. The 3:2 ratio of full-frame digital cameras is fairly close to A4, but much taller than the standard US format, which is favoured by print on demand services. But magazines come in different sizes, especially the more specialised boutique editions that are enjoying something of a renaissance.

- If an image is going to be full-page or a double-page spread, an extra 3mm is needed on each edge of the photo for what is known as “bleed”. This is printed outside of the final trim size of the publication, so that when the pages are printed, there is an allowance for movement during the printing and the trimming and binding process, so as to avoid a thin white edge on the page. It is much easier to crop the image to size than it is to add to it.

- As with page sizes, you don’t know what shape the designer will allocate for the image, which raises another issue: don’t send cropped high-res images. Send the full frame, and include a low-res crop of how you would prefer it to look, but you need to trust the art director/designer/picture editor to know how to crop the image for their needs, especially if they are paying you to use it.

- Sometimes, type will be placed on a photo, so it is better to leave some negative space around the subject to avoid it being place over the action.

- Try to avoid placing the action in the centre of the frame. If the photo is going to go on a spread you don’t won’t the subject’s face in the fold of magazine.

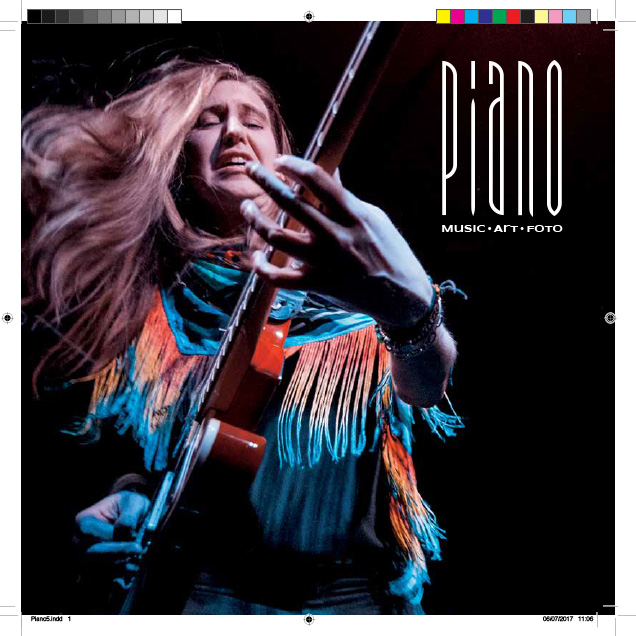

Shoot both horizontal (landscape) and vertical (portrait) images. Magazine pages are portrait shaped. You are more likely to get a single page shot published than a spread. If you want to get a cover shot, it will need to be portrait, and with plenty of space for the magazine’s masthead and cover lines. The best thing to do is to look at previous covers of the magazine to which you are submitting. The image from most modern digital cameras (around 20 megapixels) is going to be large enough to cover a double-page spread, so, in theory, it will be possible to crop it to fit the single page format, but if you can supply a full resolution vertical shot, so much the better – providing you leave enough space around the subject.

There is still a fair amount of confusion about what constitutes print resolution file. The term 300dpi is bandied around a lot. DPI (dots per inch) is essentially left over from the pre-digital days of reprographics, when different screens were used to prepare images for print. 300 dpi (or higher) was used for high-quality reproduction in art books and magazines. Newspapers, on the other hand, would use almost half that. It was calculated depending on the paper and inks used. However, an image still needs an effective resolution of 300 dpi or ppi (pixels per inch) for quality printing. A 20 megapixel file measures 5472 x 3648 pixels, which is 193cm x 129cm at 72ppi or 46cm x 31cm at 300ppi. The actual pixel area hasn’t changed, and that is the important measure. As long as the file is supplied at the size it was created it doesn’t matter if it is 72ppi or 300ppi. I have a Nikon film scanner for 35mm film that captures at up to 4000ppi. If I scan a slide at full resolution, I end up with a file that is 24mm x 36mm at 4000ppi, which is 5431 x 3551 pixels, or the equivalent of a 20 megapixel photo.

In my work as a graphic designer, I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve been sent a full-page image at 72ppi, requested it to be resent as 300ppi for print use, only to have the same file sent back, but with the resolution increased to 300ppi in Photoshop or some other image editor. All that achieves is to quadruple the size of each pixel. So basically, if you are sending an image to a magazine, send it at the full resolution it came out of the camera at. Don’t send the RAW file, and by all means colour correct it how you want to.

This raises another area of confusion. Working on the assumption that your monitor is correctly colour calibrated, and you have adjusted the colours to your satisfaction (this is even more relevant to concert photography with its multicoloured LED lights) and you end up with a vibrant image that looks amazing on your Retina screen. Chances are you will be disappointed when you see it in colour. Computer images (and that includes mobile devices) are in the RGB colour space, just like your camera. They use Red, Green and Blue to create the millions of colours and shades, and are lit from the back with tiny diodes, which is why they look so vibrant, especially the reds, blues and greens. The other thing to remember is that they will appear brighter on screen than they will in print. A printed image is made using Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black inks – commonly known as CMYK. The printed image is reflective, so you will not see those rich, vibrant colours that were on your HD monitor, especially reds, blues and greens. If it is a full-colour magazine, it is also better to convert your B&W images to CMYK to get much richer blacks. The only thing that should be printed as pure black (K 100) is type. It is possible to use additional special colour inks, but it’s not very common for magazines with diminishing budgets or in digital printing. It is also important not to confuse magazine printing, whether litho or digital, with photographic or inkjet giclee printing, which are completely different processes that will closer match what you see on screen. When sending files to a magazine for the first time, ask them for their image specs, in case they have certain requirements, as well as any ICC profiles they have.

To briefly summarise the points to consider when shooting for print:

- Shoot wider. It’s easier to crop than add to the image.

- Consider the page format when composing the shot.

- Be aware that onscreen colours are different to print ones.

All that’s left to do is find a magazine that wants to buy your photos. Of course, if you want to make your own publication using a print-on-demand service such as Magcloud or Blurb, this advice still stands, although you will be free to present your images how you want.

An older version of this article appeared on Photobite in 2017.